Regency medical practitioners

- Heather Moll

- Nov 9, 2025

- 3 min read

When you're sick in 1812, which doctor are you calling: physician, surgeon, or an apothecary? They're not the same, and they can't all be addressed with the title "doctor", either.

Let's do a quick survey of the three types of medical professionals in Georgian England.

Physicians

Physicians were the highest ranking medical professional, as well as the only ones to use the title “doctor”. Although they were not eminent medical schools, a physician needed an Oxford or Cambridge education. They did not touch patients–– other than taking a pulse or listening for a heartbeat––so they weren't considered tradespeople but gentlemen.

They were consulted in serious medical cases and diagnosed their patients. They wrote prescriptions, but didn’t dispense drugs or perform procedures themselves. There were fewer physicians than any other medical practitioner and tended to be in large cities and resort towns.

Surgeons

There were far more surgeons than physicians in Georgian England, and they had a lower status because they accepted money in return for work. They apprenticed 3-7 years rather than attend university, although some surgeons went to Scotland to train at their more prestigious medical schools.

They were the general medical practitioners people turned to regardless of whether they lived in the country or town. Surgeons treated wounds and injuries, did simple operations, and set bones. They could also diagnose illness. Some surgeons were also apothecaries and dispensed drugs.

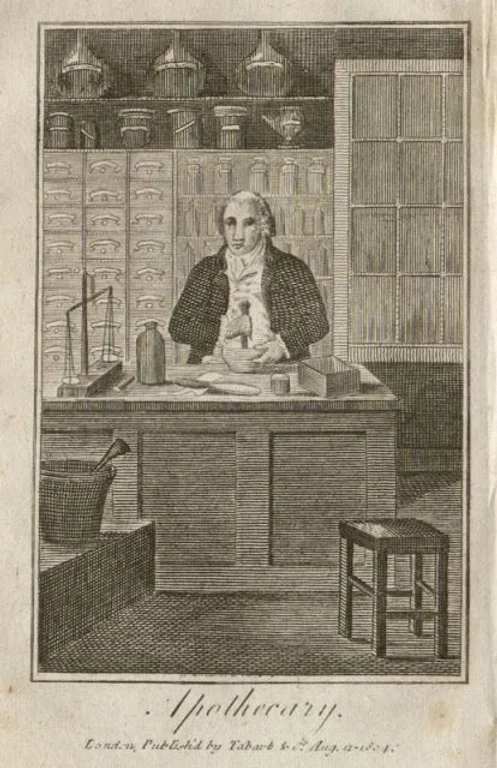

Apothecaries

They were the lowest rung of the social and professional ladder and considered tradesmen since they kept a shop and sold medicines and compounds. Some made house calls to give advice, but they only charged for any medicines purchased. If they had more training or experience, they gave their own prescriptions, but others only prescribed for a physician.

By the end of this era, all three had to be licensed. Although all could be referred to as doctors, only physicians used the title Dr.—but it was not a neat hierarchy. Some surgeons were also apothecaries, some physicians had hands-on training, some apothecaries rose in their social circles. And there were quacks at all levels who took advantage of patients.

Austen Examples

In Mansfield Park, a physician is brought in for Tom Bertram after a neglected fall (and a good deal of drinking) brought on a fever.

...she received a few lines from Edmund, written purposely to give her a clearer idea of his brother's situation, and acquaint her with the apprehensions which he and his father had imbibed from the physician with respect to some strong hectic symptoms, which seemed to seize the frame on the departure of the fever.”

In Persuasion, Anne Elliot takes charge of an accident and calls for a surgeon to help an unconscious Louisa.

"The day has produced some effects, however; has had some consequences which must be considered as the very reverse of frightful. When you had the presence of mind to suggest that Benwick would be the properest person to fetch a surgeon, you could have little idea of his being eventually one of those most concerned in her recovery."

In Pride and Prejudice, an apothecary is called to tend to Jane at Netherfield, and the idea of sending for a physician in town (just for a cold) was rejected.

“The apothecary came, and having examined his patient, said, as might be supposed, that she had caught a violent cold, and that they must endeavour to get the better of it; advised her to return to bed, and promised her some draughts. The advice was followed readily, for the feverish symptoms increased, and her head ached acutely.”

Medical men from all three tiers appear in Austen's novels, from the three physicians who attended a dying Mrs. Tilney to the apothecary-surgeon who sets young Charles Musgrove's dislocated collarbone. There are the imaginary ailments like those of Mr. Woodhouse along with serious illnesses, like Marianne Dashwood's "putrid fever".

Austen generally depicts them as reliable and hardworking, but faith in their abilities often varies by character. Mr Woodhouse depends heavily on Mr. Perry whilst Lady Denham from Sanditon proudly states, "Here have 1 lived seventy good years in the world and never took physic

above twice—and never saw the face of a doctor in all my life on my own account."

But we're left to imagine what sort of doctor she meant, physician, surgeon, apothecary, or if she meant all three.

And there were still quacks at al levels who took advantage of patients.